China: Dissident writer and PEN member takes own life because of persecution by PRC government

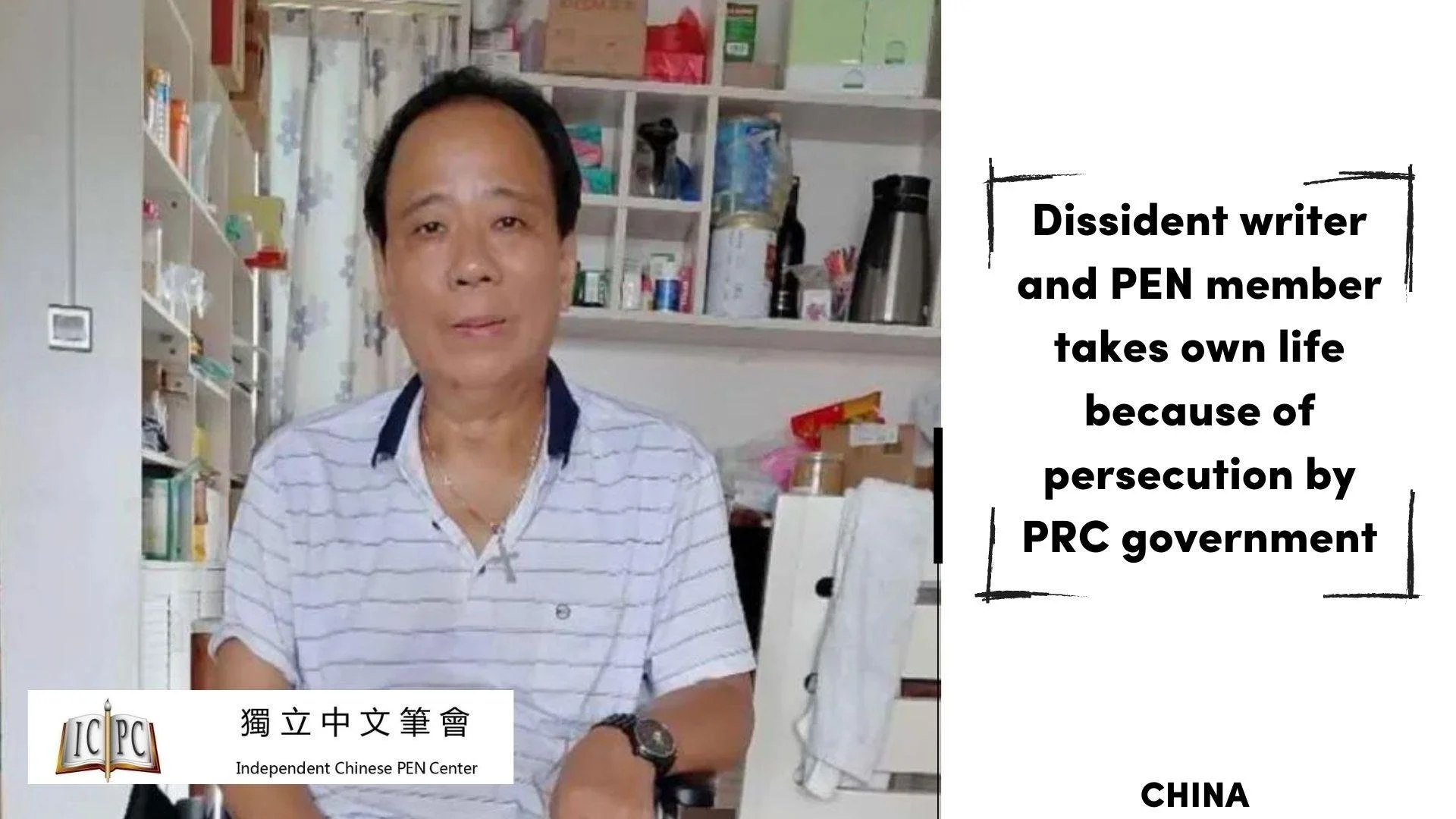

The PEN community mourns the death of writer and ICPC member, Li Liqun (pen name, Li Huizi 李悔之)

PEN International and the Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC) are deeply saddened by the passing of dissident writer, political commentator, and ICPC member, Li Liqun (pen name, Li Huizi 李悔之), who took his own life on 23 July 2021. Li’s untimely death is a tragic example of the human cost of the PRC government’s repression of free expression throughout China. We call for an immediate end to the persecution of writers and intellectuals who have been wrongfully targeted for their peaceful expression.

Li was a writer, political commentator and public intellectual. In 2008 he began publishing his writing on Chinese-language news sites including Boxun, Phoenix and Sohu. He became one of the most widely read authors on those platforms, and from 2009 Boxun recognised Li as one of China’s top 100 public intellectuals for three years in a row. In 2012, many of these platforms were censored by the PRC government, and in that same year Li became a member of ICPC, which continued to feature his writings on the ICPC website and shared hundreds of his blog posts on the Centre’s Membership Collections page. Li regularly participated in Centre activities, including attending a ‘Taipei Writers Week’ in 2015. After suffering a cerebral haemorrhage in March 2020, ICPC provided Li with financial support, and its Vice President, Zhao Shiying, visited Li’s home to offer his greetings and solidarity on the Centre’s behalf.

Li Liqun’s tragic death is a painful reminder of the devastating toll that the Chinese Communist Party’s authoritarian rule continues to impose on writers and public intellectuals in China. Since Xi Jinping came into power in 2012, the country’s censorship apparatus has evolved considerably, providing the state with unparalleled coercive powers to monitor communications and impose severe restrictions on those deemed to have engaged in problematic expression.

On the eve of his death, Li sent out a suicide letter to some of his friends online before breaking off contact with them. His letter begins by highlighting how he was once rated as one of China’s most influential public intellectuals for his online writing, in which he frequently called for ‘fairness and justice’ and argued for political reform in China. However, since Xi Jinping’s rise to power, he noted the country’s narrowing space for free speech.

In 2017, during the Chinese Communist Party’s 19th National Congress, Li was designated as a target for 'stability maintenance' (weiwen 维稳), a highly coercive practice used to repress dissidents which is frequently deployed during times of heightened political sensitivity. Measures taken against those targeted typically include increased levels of surveillance by local security officials and can involve various forms of detainment, including house arrest or even forced relocation. As a result of being targeted, Li’s phone was monitored, and he had to report his movements to public security officials who also had the power to deny any meetings with Li’s friends. On several occasions, invitations by Li’s friends to meet him were blocked by the authorities.

The cerebral haemorrhage that Li suffered last year left him partially paralysed on the right half of his body, making him reliant on crutches and a wheelchair. A few months later when he relearned the ability to use his left fingers which allowed him to resume his typing, he published an essay titled My View of Life and Death. In the essay, he commented:

‘Recently as a result of my life’s misfortune, my view on life and death seems to have suddenly matured... Confucius said, "while you don't yet understand life, how can you understand about death?” but I am the one who "has known about death at first, and then about life". This is also Heidegger's countdown method in the sense of life, "being towards death", which is my view of life and death and my philosophy as well.’

Despite Li patently representing no risk to China’s internal stability, his requests to be removed from enhanced surveillance were repeatedly denied. Increasingly isolated and made a virtual prisoner in his own home, Li was repeatedly visited by security officials, a common intimidation tactic experienced by dissident writers and public intellectuals.

In his letter, Li noted that he never had anything to hide with his writing, which he argued was within the scope of the freedoms permitted within the PRC’s constitution. Since suffering from the cerebral haemorrhage, Li stated that he hadn’t engaged in any critical expression for over a year, yet the levels of surveillance and harassment continued to escalate. In the weeks before his death, Li received calls from security officials who also followed him on social media, a chilling tactic routinely used to silence dissidents by forcing them to exercise self-censorship online.

Li’s letter concludes with him saying that he would ‘commit self-denial from the Party and the People’, a term used to criticise people for taking their own lives during the Cultural Revolution, and that the upper levels of the security services are responsible for his suicide. His final wish was for his ashes to be poured into the Dongjiang river.

To the PEN community, Li Liqun will be remembered as he had come to view himself a year ago, as ‘Being towards Death.’

For further information please contact Ross Holder, Asia Programme Coordinator at PEN International, Unit A, Koops Mill, 162-164 Abbey Street, London, SE1 2AN, Tel.+ 44 (0) 20 7405 0338, email: ross.holder@pen-international.org